David Bowie & the Problem of Puzzles

David Bowie died 10 years ago today. He would have been 79. Yesterday was his birthday and the 10 year anniversary of his final album, Blackstar. With the blessing of time, I can look back and say that's truly one of my favorite albums of his and consequently one of my favorite albums. At the time, it was just painful and on constant loop in my car. In fact, I didn't listen to any other artists for a year following his death. And I can't begin to tell you how many people called me the morning of his passing to ask me if I was okay. So many folks knew it was going to hit me hard. Which it did.

There was a tweet I saw around that time, or maybe I saw it paraphrased, but it expresses my reaction perfectly:

"Thinking about how we mourn artists we've never met. We don't cry because we knew them, we cry because they helped us know ourselves." — Juliette (@ElusiveJ) January 11, 2016

There are a thousand reasons he was important to me, but the fearless creativity and the distrust of being comfortable in one arena really informed my own journey from playwright to journalist to screenwriter to editor to children's author to game designer/game publisher, a journey that took me from Birmingham to Oxford to London to Chicago to Los Angeles to San Francisco and finally back to Birmingham. I've pushed myself into new areas and said "yes" to things I wanted to say "no" to (out of fear) because of this Bowie mantra:

“If you feel safe in the area you’re working in, you’re not working in the right area. Always go a little further into the water than you feel you’re capable of being in. Go a little bit out of your depth. And when you don’t feel that your feet are quite touching the bottom, you’re just about in the right place to do something exciting.”

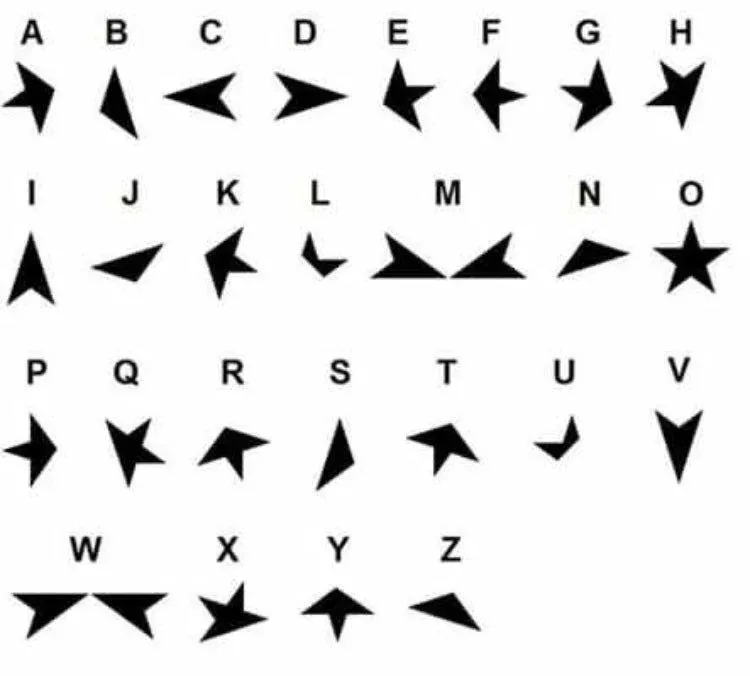

I don't remember how long it was before I realized the cut up star on the album cover spelled "Bowie", but I do remember the moment. It was like a little puzzle opening up. Which isn't a great segue, but will have to do...

Because recently I've been thinking about puzzles in roleplaying games. The brilliant Mike Shea, on The Lazy RPG Podcast, stated that he didn't like puzzles. Mike had a variety of reasons—the amount of effort they require verses the reward (in terms of game fun) they provide, the way they can close off a portion of the adventure unless and until the puzzle is solves, how the solving of the puzzle is a "player thing" and not a "character thing," if the puzzle contains a trap, how does it reset or, if it doesn't reset, does that mean that the adventurers are the first to ever attempt it? All valid objections.

But the one that stuck with me the most is that it begs credibility. Who has created this puzzle and why? If the goal is to, oh, protect your treasure, a really good lock or a password only you know does a much better job. Why would you create a mechanism for opening your treasure vault and then put instructions on the wall next to it detailing how to open the vault? That's not very smart.

As I pondered this, I realized there were only about two occasions where I could excuse a puzzle.

The first is dwarves. Particularly, especially Old School Dwarves. Not the ones who live in cities. Not the ones who fly around in airships or sail the seven seas. I'm talking about the rock loving, mountain dwelling traditionalists. I think those guys love making elaborate—fiendishly clever—puzzle traps for their hoards, and then bragging about it to their fellows. In other words, I think there is a whole subculture of dwarven puzzle geeks. So puzzles in ancient dwarven holds get a pass from me.

Still, that's a well you can only draw from one, maybe twice.

The other time when I think puzzles make since is when a cult, secret society, or religious order wants to tuck something away, not for a rainy day, but for the ages. To explain, let me step away for a moment.

Stories are time-binding. What this means is, stories encode truths. They trap truths like flies in amber, where they stay locked in for centuries, waiting for someone else to chip it out. Stories were designed this way from the beginning. They exist so that truths can be extracted and understood regardless of the shifting meaning of words, the drift in languages, the ever-and-rapidly-changing cultural context. Stories were designed to survive societal upheavals across centuries. This is also why stories are such amazing teaching tools. Why a story can communicate a truth, even-and-especially an unpleasant one, where mere data and fact might hit a brick wall in someone's head.

I could go on about this, but I'll pull us back.

Say you were a secret order who had just used a super powerful weapon to defeat the Dark Lord, and you didn't want that weapon hanging around and unbalancing the world after the battle was over. But...you were worried that someone might need it again one day, the next time there was a Dark Lord that needed smiting. You have to lock it away. And not with a padlock in a safe in your basement. Because you really want this thing out of the way. You don't want Sedrick, the junior mage you don't quite trust though you can't put your finger on exactly why, just going and getting it out of storage to see what it can do. So you have to lock it up good and make it hard to get.

But you know it could be centuries, millennia even, before your order really will need that weapon. And you know that language changes. Culture changes. People change. Countries change. So how do you leave a key that will be understood? And how do you know your order will even exist in 1000 years? And if it doesn't, how do you ensure that the key is understood by the right people and not the wrong ones?

You time-bind that key in a story. You have a narrative that teaches your values. And, unless the puzzle-recipient understands or has learned those values, they can't figure out the puzzle. Context is key, and then you spend a little time teaching that context.

This is, interesting, how I handled puzzles in my second novel, Nightborn, where a very powerful whatsit has been hidden away by a secret order. It's also, incidentally, the fifth season of Star Trek: Discovery. Which is my favorite Star Trek series, not least of all because they sang "Space Oddity" in the Season 2 episode "An Obol for Charon."

And with that circle coming round, I'll say goodbye for now. And I'll say that I hope that today we'll all go a little further into the water than we feel we're capable of being in.

Have a great weekend, all you pretty things.